Secure Route 53 healthchecks using HAProxy

TL;DR: It’s possible to configure HAProxy to have separate health check and service endpoints, allowing to set up different firewall rules for each. Scroll down for config samples.

Case outline

When designing a highly available service on EC2, AWS Elastic Load balancers are quite often a key component. A common setup is to have an internet facing ELB forward requests to EC2 instances that are in a private subnet, not directly accessible from the internet. Recently though, we encountered a scenario where we couldn’t use ELBs as they can’t have a fixed IP (Elastic IP in AWS terms).

The elastic IP requirement

Originally the service, a dashboard of sorts, was restricted to the office network and a limited number of supplier office networks, so whitelisted to a set of IPs. In these times of remote working, this was no longer a maintainable strategy so we needed to grant access to traffic originating from the office VPN, allowing access also to remote workers.

In our office’s VPN configuration, internet traffic is by default not routed over the VPN connection. So the office automation department needed to know what the IPs were, in order to configure VPN clients to route traffic to the service over the VPN as well. This way we could setup firewall rules to grant access to the VPN exit nodes, but it also meant we needed to look for alternatives to our ELBs.

The HA in HAProxy

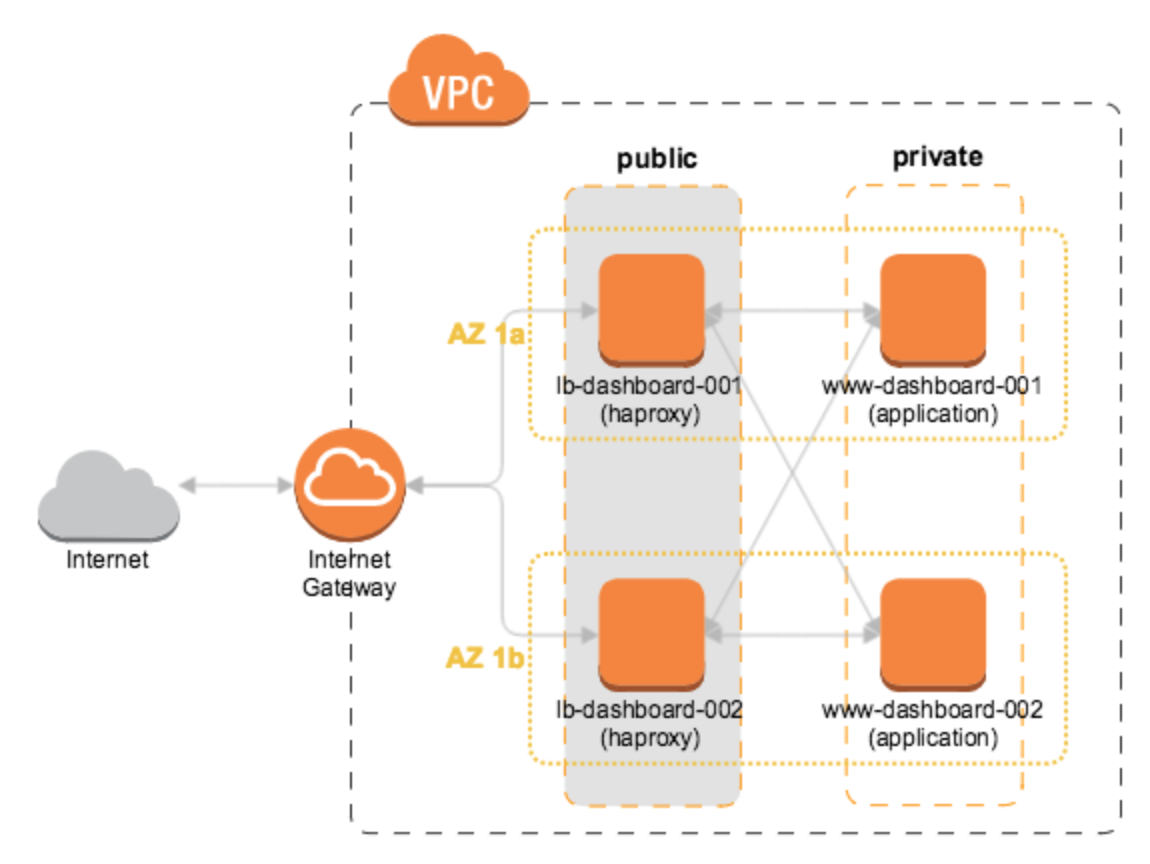

As we already had (good) experience with HAProxy, the most apparent approach was to replace the ELB by HAProxy running on an EC2 instance in one of our VPC’s public subnets. However, ELBs are by design ‘highly available’, yet a single EC2 instance is not. So we needed at least 2 of them, in different availability zones.

AWS Diagram: HAProxy load balancers in public subnets of multiple availability zones

Route 53 healthchecks

To prevent half of the traffic going to the /dev/null of the internet, this required having Route 53 health checks in place that will stop traffic going to a load balancer in case of failure or reboots due to maintenance. Straightforward if it weren’t for the firewall rules that will only allow traffic originating from our VPN…

Summarizing the case

- Office VPN requires application to have fixed IPs when on public internet, to specifically route traffic to it over VPN.

- Having the application only accessible from internal network not an option, because of certain allowed parties not having access to he office network.

- ELBs no longer possible due to fixed IP requirement.

- Setup needs to be highly available.

Of course the situation would be easier if we could simply limit access to an internal network that has a route to our VPC. No need for fixed IPs, no need to whitelist VPN exit nodes. Reality however is different and there are some aspects we as a team have no control over.

Possible solutions

After brief research, possible solutions boiled down to:

- Whitelist known Route 53 health check IPs.

- Find a way to only publicly expose a monitor endpoint that reflects the service health.

Whitelisting Route 53 health checks, using the IPs referred to by the AWS developer guide is arguable the cleanest solution. It introduces however, some ‘moving parts’:

- Periodically querying the Route 53 health check IP list and updating a security group.

- Monitoring to ensure this mechanism works well.

If possible, less moving parts is preferable, especially as this in our stack is an uncommon requirement. So let’s see what’s possible.

HAProxy health checks

As it turns out, HAProxy doesn’t disappoint and has some very powerful configuration directives that allow decoupling the monitor from the frontend.

Without further ado (there’s been enough already in preceding paragraphs), the resulting HAProxy config:

global

chroot /var/lib/haproxy

daemon

group haproxy

log 127.0.0.1 local0

log-send-hostname lb-dashboard-001

maxconn 5000

pidfile /var/run/haproxy.pid

stats socket /var/lib/haproxy/stats

user haproxy

# SSL/TLS configuration

tune.ssl.default-dh-param 2048

ssl-default-bind-options no-sslv3

ssl-default-bind-ciphers HIGH:!MD5:!aNull:!ADH:!eNull:!RC4:!NULL:!CAMELLIA:!AECDH

ssl-default-server-options no-sslv3

ssl-default-server-ciphers HIGH:!MD5:!aNull:!ADH:!eNull:!RC4:!NULL:!CAMELLIA:!AECDH

defaults

log global

maxconn 5000

retries 2

stats enable

mode http

balance roundrobin

timeout connect 3000

timeout server 120s

timeout client 120s

frontend dashboard_https

bind 0.0.0.0:443 ssl crt /etc/haproxy/ssl/dashboard.pem

reqadd X-Forwarded-Proto:\ https

default_backend dashboard

frontend route53_monitor

bind 0.0.0.0:50000

acl site_dead nbsrv(dashboard) lt 1

monitor-uri /health

monitor fail if site_dead

backend dashboard

balance roundrobin

option httplog

option allbackups

option httpchk GET /health

server www-dashboard-001 10.100.0.1:80 check inter 2000 rise 3 fall 5 backup

server www-dashboard-002 10.200.0.1:80 check inter 2000 rise 3 fall 5

listen stats

bind 0.0.0.0:8080

mode http

balance roundrobin

stats enable

stats show-node lb-dashboard-001

stats hide-version

stats uri /

stats realm Strictly\ Private

stats auth user:supersecret

stats refresh 5s

The important part is frontend route53_monitor. What happens here:

- It binds to a different port than

frontend dashboard, allowing to apply different firewall rules to each port. - Using acl and nbsrv it tests for the number of healthy backends, if below 1, it sets

site_dead. - It configures a monitor endpoint using monitor-uri.

- Using monitor fail, it configures the monitor to report failure based on the test result stored in

site_dead. - The route53_monitor frontend has no

default_backendconfigured (and it’s not configured in default section either), so any request on the monitor port other than/healthwill hit a 503.

Route 53 configuration

The DNS part of the Terraform configuration, comments per resource explaining the purpose:

# Host-specific A records for both load-balancers

resource "aws_route53_record" "dashboard-record" {

zone_id = "<my-zone-id>"

count = 2

name = "dashboard-lb-${format("%03d", count.index + 1)}.production.mydomain.nl"

type = "A"

ttl = "60"

records = ["${element(aws_instance.lb-dashboard.*.public_ip, count.index)}"]

}

# Health checks for each of the load balancers

resource "aws_route53_health_check" "dashboard-healthcheck" {

ip_address = "${element(aws_instance.lb-dashboard.*.public_ip, count.index)}"

count = 2

port = 50000

type = "HTTP"

resource_path = "/health"

failure_threshold = "5"

request_interval = "30"

tags = {

Name = "dashboard-${format("%03d", count.index + 1)}.production"

}

}

# Group consisting of 2 alias records to the host records, with associated health checks, having weighted routing

resource "aws_route53_record" "dashboard-group" {

zone_id = "<my-zone-id>"

count = 2

name = "dashboard.production.mydomain.nl"

type = "A"

weighted_routing_policy = {

weight = "50"

}

health_check_id = "${element(aws_route53_health_check.dashboard-healthcheck.*.id, count.index)}"

set_identifier = "dashboard${format("%03d", count.index + 1)}"

alias {

name = "${element(aws_route53_record.dashboard-record.*.fqdn, count.index)}"

zone_id = "<my-zone-id>"

evaluate_target_health = true

}

}

Wrapping it up

As a result:

- If one of the two load balancers goes down, it will be removed from DNS. (Note that for planned maintenance we could disable the health check first, allowing it to handle requests until DNS directs traffic to the other load balancer)

- If a load balancer can’t reach any of the two dashboard web servers, it’s health-check will report

FAILand it will be removed from DNS. As a result dashboard web servers can safely be restarted. Here too, for a more graceful experience, health check on the dashboard servers can be made to reportFAILbefore the service actually stops. - If a load balancer can’t reach any of the dashboard servers, it’s health check will report

FAILand it will be removed from DNS.

As already mentioned, excluding health checks from access restrictions is arguably not the best solution. It’s the trade off for having a simple, low-maintenance setup. Sometimes it’s acceptable to ‘let things become a problem first’. This setup has been running without any issues in our stack for over a year now.