EFS Excess - Cleaning up terabytes of data

Recently we discovered that what used to be a minor line in our monthly billing graph, had become several strokes wider, amounting to a couple of hundred dollars on the monthly bill. This line represented EFS, wich we use, but by no means in large amounts.

So we thought…

As it appeared we were using around 3 terabyte of data.

Investigating

We use EFS as our go-to persistent storage solution for applications in EKS, its main benefit being that it spans all availability zones so scheduling of pods remains simple. Nearly all applications are stateless and use Elasticache or RDS to store data, so the number of applications that use persistent volumes are limited, and for the applications that do use it, requirements are not high. Examples of applications that use EFS include Jenkins, Grafana and Prometheus.

We provision an EFS volume and configure efs-provisioner accordingly for each EKS cluster (We’ll probably switch to EFS CSI Driver or EFS CSI dynamic provisioning at some point). The beauty is that providing an application with EFS storage is as simple as specifying a storage class. A side-effect is that AWS tags give no additional information as to what application in the cluster is using excessive storage.

Accessing EFS

So, we can peek into the individual EFS PVCs currently used by pods to figure out what application uses a large amount of storage. But it’s quite cumbersome and maybe data was added by an application that no longer exists. So the most thorough way is to mount the entire EFS volume and explore that.

That can be accomplished by adding a temporary deployment similar to this:

# kubectl apply -f this_file.yaml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: awscli-efs-mount

labels:

manual_install: "1"

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: awscli-efs-mount

app.kubernetes.io/instance: default

template:

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: awscli-efs-mount

app.kubernetes.io/instance: default

spec:

containers:

- name: default

image: "amazon/aws-cli:2.0.59"

command: ['cat']

tty: true

volumeMounts:

- name: efs-volume

mountPath: /mnt/efs

volumes:

- name: efs-volume

nfs:

server: <EFS-ID>.efs.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com

path: /

And start a terminal session within the pod, e.g.

kubectl exec -it awscli-efs-mount-xxxxxxx-yyyyy -- bash

If needing more fine-grained control over nfs mount options, since the nfs volume type offers no options, you could mount the EFS volume from within the pod, however this requires the pod to run in privileged mode. (We initially went in this direction, but in our case the above simple way worked yust fine.)

# add security context to the 'default' container from previous example

containers:

- name: default

# ...

securityContext:

privileged: true

Then within the container run:

yum -y install nfs-utils

mkdir /mnt/efs

mount -t nfs -o nfsvers=4.1,rsize=1048576,wsize=1048576,hard,timeo=600,retrans=2,noresvport <EFS-ID>.efs.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com:/ /mnt/efs &&

Note:

- In the above example I use the

amazon/aws-cliimage. It just happened to be an image I recently fiddled around with. Use any image you are familiar with that provides a shell. - Use a container running the user root. Normally not the best of practices but here you need to be able to navigate a filesystem with varying ownership.

Looking around

Looking at the EFS mount you can clearly see directories that map to PVCs in the cluster:

# ls -al /mnt/efs

# (example result)

drwxrws--x 3 root 40003 6144 Jul 6 2020 sitespeed-grafana-pvc-pvc-28782e8e-bf8c-11ea-8b69-0249b4a9a724

drwxrws--x 3 root 40004 6144 Jul 6 2020 sitespeed-graphite-pvc-pvc-28782b57-bf8c-11ea-8b69-0249b4a9a724

drwxrws--x 5 root 40005 6144 Jul 6 2020 sitespeed-influxdb-pvc-pvc-28781b92-bf8c-11ea-8b69-0249b4a9a724

The most straightforward way to check usage would be running something like du -h -d1 ./ from /mnt/efs. But given the amount of storage used this will probably never complete unless you’re lucky and the disk usage is a limited number of large files. So use a combination of:

- Exlusion. Any folder quickly returning a result from

du(that’s not a very large amount) is not the one we’re looking for. - Drill down. Enter any directory where

dudoes not give a result within a reasonable time and explore its contents. - Use commands like

ls -alorls -al |wc -lto get an impression on the amount of files and directories within a specific directory.

Findings

As it turned out, the PVC used by the Sitespeed Graphite component was the one holding terabytes of data. We use Sitespeed to measure browser performance of our site and several similar sites. Graphite stores metrics in a whisper database, which on disk is stored as ~150Kb sized files in a directory structure:

# example directory:

<pvc-root>/whisper/sitespeed_io/desktop/summary/www_nu_nl/chrome/cable/aggregateassets

# ...containing hundreds of thousand subfolders like this, each containing about 1.5Mb of data in `.wsp` files, example:

<pvc-root>/.../aggregateassets/https___www_nu_nl_static_bundles_js_app_0fef8dda_js/contentSize.wsp

This raises some questions:

- Can we safely delete old files?

- Why aren’t old files deleted in the first place?

About the first question, several resources (albeit quite dated) suggest that old metrics can simply be removed by deleting old *.wsp files.

The reason Whisper data is not cleaned up is not clear yet. We’re probably overlooking something since our storage_schemas.conf suggests data shouldn’t exceed the age of 30 days. (Sitespeed docs and Graphite docs). That’s one for the backlog, assuming deleting old files provides an intermediate solution.

Fixing

Since it’s EFS, we can’t access the underlying storage other than via the network to quickly delete entire folders. Deleting content boils down to iterating and deleting individual files, which is slow.

Another theoretical option would be to discard the entire EFS volume and move the contents that we want to keep to a new volume. However, determining what Graphite data to keep (although starting with an empty DB is an option here) is also time consuming. Most importantly, replacing the underlying nfs volume of several PVCs that are actively used is a surgical opereration that would need thorough testing. That would be time consuming as well.

So the starting point will be trying to purge old data via some cli commands. Long story short: It’s slow but it works.

The commands that accomplish our goal:

# Enter dir that needs cleaning

cd <pvc-root>/whisper/sitespeed_io/desktop/summary/www_nu_nl/

# Delete files older than 14 days.

# Leave out the delete print part if not needing visual confirmation that it's 'doing something'

find ./ -type f -path "*.wsp" -mtime +14 -delete -print

# Delete empty folders

find ./ -mindepth 1 -type d -empty -delete -print

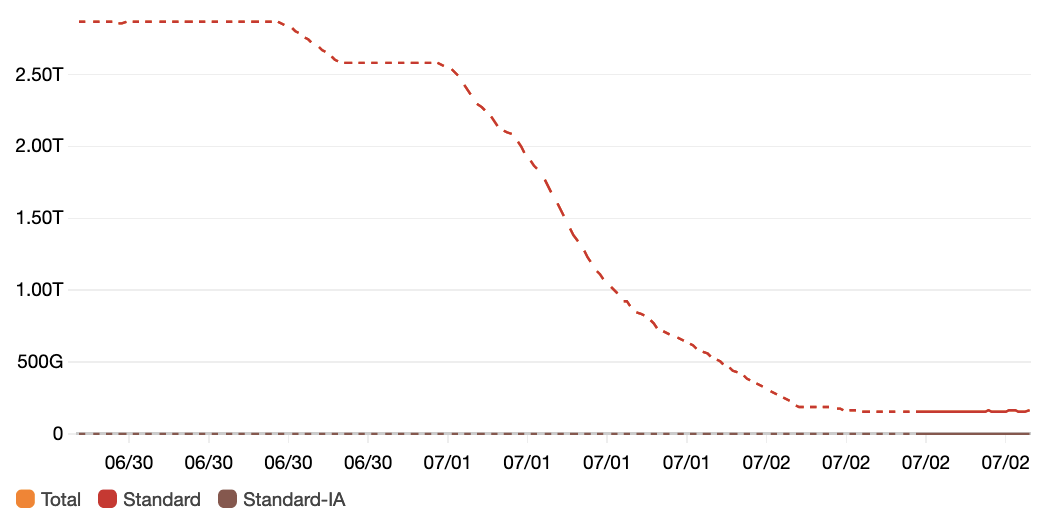

EFS Storage bytes

After the initial cleanup that takes days, above commands were easily setup as a cronjob.

Some tips:

- Run several commands in parallel to speed up the operation. In our case we analyse multiple sites, each having its own directory. This allows running

find -deletecommands in parallel, while still keeping track of what folders have been already processed. In the graphs below the higherPercentIOLimitvalues correspond with more parallel delete operations. - If deleting of files is aborted, alternate with deleting empty dirs to avoid

findfirst examining tons of empty directories. - Keep an eye out on EFS metrics. You don’t want to cripple applications by exceeding I/O capacity. See graphs below:

EFS BurstCreditBalance

EFS PercentIOLimit

EFS PermittedThroughput

Summarising

Take-aways:

- Preventing is easier than fixing. Set up Cloudwatch alerts for exceeding a certain EFS storage size. Alternatively look at billing alerts.

- Check if assumptions about what a configuration setting does, actually hold up. In a case like this: Set a reminder for a couple of days after the configured max age to see if storage is actually cleaned.

As it shows, not all days at the office are equal: There’s building, but sometimes there needs to be (less exciting) cleaning. There seems to be no magic trick to speed up a EFS clean-up operation like this, outside of perhaps swapping out the EFS volume that backs the storage class. Perhaps some of the described steps save somebody some time, or at the very least provide a mildly entertaining read.

I wouldn’t be surprised if there are more efficient ways to handle this type of problem, so if you have a good tip to spare or other feedback, find me on Twitter.