Shifting left using feature deployments

Introduction

Feature deployments can help teams to validate work in progress, and test pull requests before merging. This article will address some things to consider when setting up feature deployments. Furthermore, an implementation in use at NU.nl based on AWS, Kubernetes, Helm and Akamai, will be described.

Parallel tracks. Source: Bing Image Creator

In this article:

The use case for feature deploys

Once teams grow, you might have multiple people working on a single application. Ideally, one wants to integrate often (the ‘continuous’ in CI), yet at the same time, one usually wants the have the main branch in a deployable state.

So, how do you validate that a pull request results in a deployable application? Tests, very much preferably automated tests.

But once there is a more visual or UX aspect to the application, fully automated testing can be surprisingly hard. Similarly, collaborating with other departments might complicate testing.

If there is just a single test environment, the testing lane easily becomes a traffic jam: Lots of alternating deployments of branches, a lot of alignment between team members, and the ever-present question “Is my feature that I presume I am currently testing, really still on test?". Slow, error-prone, and full of overhead.

Feature deployments, also sometimes referred to as ‘preview deployments’ can help shorten the feedback loop and avoid this traffic jam: Every feature branch will be deployed in a separate environment.

Another reason a single test environment might not suffice is when needing to have a representative environment for automated end-to-end tests before merging into the main branch.

Examples of situations where we have found feature deployments to be useful are:

- How does this feature look? (to someone not able to easily spin up a local development environment)

- Is this swipe gesture smooth?

- Does the navigation still work when banner slot X is filled? (Needing a representative environment for e2e tests where advertising can be integrated)

- Does platform x receive the expected events?

- Does this API work-in-progress align with the feature developed in the mobile app?

Feature deployments: An anti-pattern?

Modern practice encourages us to keep features small, merge often and fast, and automate everything. Yet we are considering feature deployments that, while ideally just for automated end-to-end tests, might result in branches being preserved until some non-automated procedure is finished? Should we really?

Probably the most important thing is to never consider feature deployments a goal but merely a means to an end. If feasible, putting effort into automation, removing the need for feature deployments, would be preferable.

Speaking in favor of feature deployments: It aligns with the shift left paradigm. We try to validate our work as soon as possible. If that involves stakeholders that can’t be automated, validating before merging and proceeding further down the delivery pipeline sounds reasonable.

Alternatives

Some alternatives might be worth considering:

Feature flags

Feature flags decouple deployments from the actual release. This opens up the possibility for a more rigorous form of trunk-based development. Work in progress will be continuously deployed. Only when it is finished will it be released to the public via a feature flag.

Feature flag platforms can typically release features to segments, like company users, or beta testers. This way, certain aspects can be tested in production before releasing them to the general public.

Moving development into the cloud

When development work in progress happens in the cloud, or is closely integrated with the cloud, the ‘deploy’ step can become an integral part of the workflow to the point that it disappears completely. Tools like Raftt, Telepresence, and Mirrord aim at improving the development experience, including preview URLs.

Likewise, serverless development, unless using something like LocalStack, often happens in the cloud, making the availability of the work in progress ubiquitous.

Define scope

So, once we have established feature deployments solve a problem, we arrive at the next question: What should be included in a feature deployment?

Applications are hardly ever isolated. They consume services, use databases, and emit or consume events. Those services, in turn, also have dependencies; the list goes on.

Determining what to include in a feature deployment will involve trade-offs and pragmatism. Some questions that might pop up:

- Can we easily provision and populate a dedicated database? The provisioning time of a RDS Aurora cluster is ~20 minutes. Do we consider that easy? Is it cheap enough? Once provisioned, can we easily load a fixture dataset?

- If so, can we fully leverage the database? Ideally, databases are used by a single (micro)service. However, the landscape is not always ideal, and other applications might be needed to write to the database, increasing our scope.

- Do we need to have per-feature deployments of supporting services?

- If not possible, for example, when integrating with a SaaS, should we setup additional tenants (if possible)?

- When sharing a supporting service with other feature deployments, will our testing efforts interfere?

- Are there parts of our infrastructure we can not easily create duplicates for?

- Are there services we integrate with that can not handle multiple domain names? Example: A consent platform using redirects. Can it be configured to accept a wildcard domain as a valid return URL? Alternatively, does it have an API to (un)register return URLs? If not, can we disable this integration?1

Rule of thumb: Keep the scope as small as possible. It will probably be easier from a devops perspective and easier to reason about.

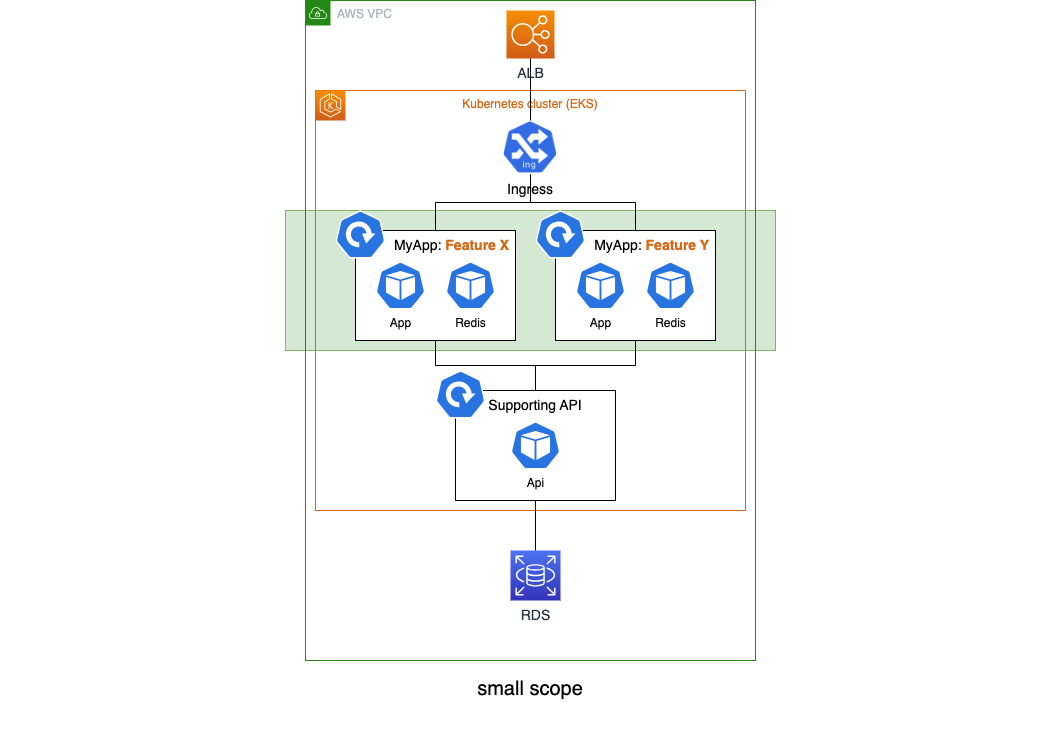

To illustrate, small scope:

Small scope

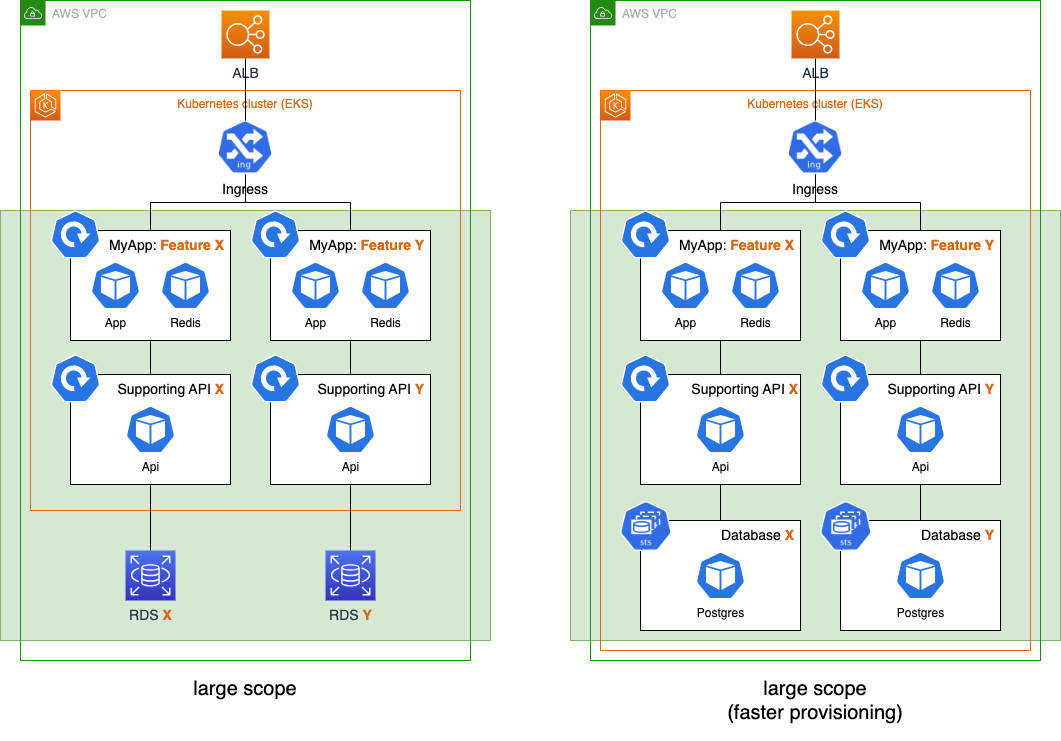

And large scope. Note how choosing to deploy a relational database as a container can greatly speed up and reduce the operational complexity of the feature deployment:

Large scope variations

Example implementation

Let’s take a more in-depth look at the feature deployment setup for the BFF (Backend for Frontends) that is used by our mobile apps.

To address the ‘should we?’ question: An API returning JSON is typically easy to test in a fully automated way. However, we still get value out of feature deployments:

- Teams are cross-functional. While one developer works on the API part, mobile app developers can work on corresponding changes based on the feature deployment.

- We can use the feature deploy to run e2e tests.

- We control many aspects of service integrations via the BFF, such as advertising and event tracking. Sending the intended data can be unit tested, but ensuring it is the correct data often requires some back-and-forthing with other departments. Feature deployments help us in shorten that feedback loop and ensure correctness before we ship.

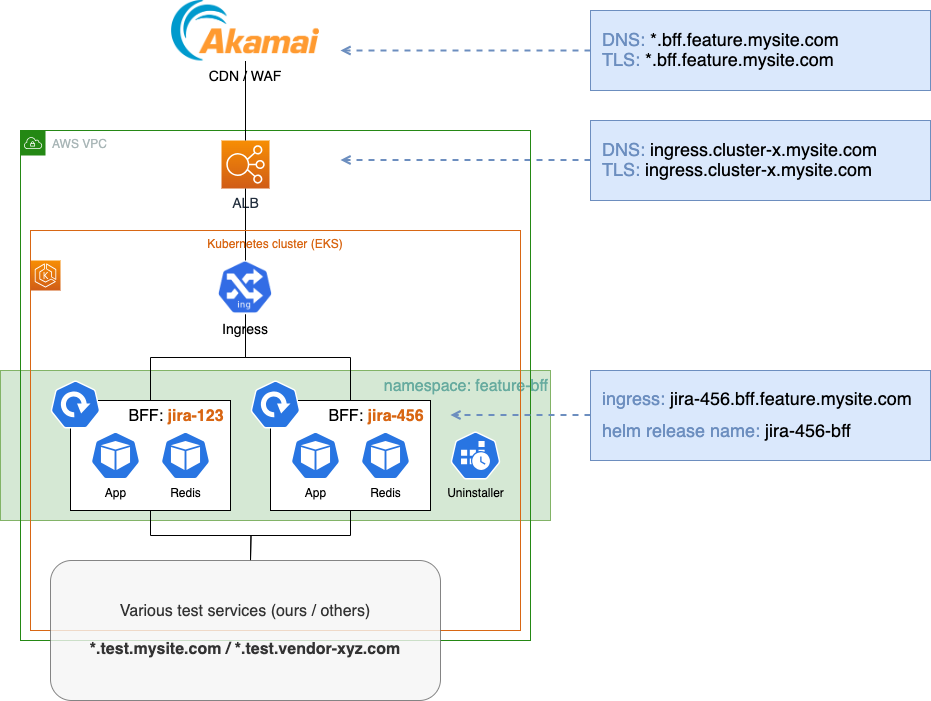

Our feature deployment setup looks like this:

Sample implementation

Let’s go over some parts

Akamai

As written previously, it is valuable to have a representative testing environment as early as possible in the development lifecycle. And being representative means including the CDN, which may contain logic related to caching, redirects, and cookie handling.

Setting up an Akamai property takes about 15 minutes. That’s not fast. Furthermore, specific to Akamai, there are some hurdles related to setting up properties that support secure by default. Adding to that, DNS records need to be setup for the edge host and for validating the TLS certificate. That is all possible to automate, but not particularly easy, and doing so does introduce a lot of moving parts.

We found that setting up a single property shared by all feature deployments works best. It’s a one-time setup, not affecting the speed of any of the feature deployments. Caching is unique per feature since the cache key includes the host name. All traffic goes to Kubernetes ingress, and only there is the split made to the separate feature deployments.

This setup involves some use of wildcards:

- A wildcard DNS entry to the CDN, e.g.

*.bff.feature.mysite.com CNAME bff.feature.mysite.com.edgekey.net. - A wildcard certificate on the CDN, in this example

*.bff.feature.mysite.com

CDNs typically accept TLS certificates from origins that match either the requested Host or the origin FQDN. We terminate TLS on an AWS ALB and use the origin (ALB) FQDN.

Helm unique release names

By convention, our feature branches reference the Jira issue we are working on. So branches will be named something like feature/JIRA-456_something_descriptive. CI/CD will parse this issue from the branch name, and apply it to our Helm install in the following ways:

- Helm release name. Prefixing the release name with the issue code ensures all Kubernetes object names are unique within the namespace. For example, a release name of

jira-456-bffwould result in deployments namedjira-456-bff-appandjira-456-bff-redis. - Ingress hostname:

jira-456.bff.feature.mysite.com - Application config, things like the redis service-name if redis is included in the feature deployment, hostnames the application accepts, etc.

Uninstaller

With pipelines adding more and more feature deployments, there needs to be a mechanism that removes these deployments at some point.

In each feature namespace we deploy a cronjob that:

- Consists of some python code and the

helmbinary - Contains some logic that determines the current namespace and evaluates the

updatedvalue of the helm releases it finds - Role binding that grants it admin permissions within that namespace

This allows to:

- Run a cronjob every evening without evaluating

updated. Fast cleanup but requires redeploy when resuming work the next day. - Run a cronjob more frequently but only uninstall when

updatedis a certain number of hours (or days) in the past.

Python uses subprocess.run to invoke the helm binary, as shown below:

def _helm_list_releases(namespace):

# Controlling time-format, since default output can't be parsed by dateutil

cmd = f'helm -n {namespace} list --time-format "2006-01-02 15:04:05Z0700" -o json'

return json.loads(_exec_cli_cmd(cmd))

def _helm_uninstall(namespace, release_name):

cmd = f"helm -n {namespace} uninstall {release_name}"

_exec_cli_cmd(cmd)

Resource usage and cost

Non-production capacity tuning can be somewhat challenging: A lot of the time throughput is absent, yet having very low CPU limits will badly affect any request. In our experience, what works well is to have very low CPU requests, say 0.05 cpu and no, or a sufficiently high, limit. This works because:

- CPU is compressible, so when there is a brief period of CPU saturation, performance degrades but nothing will break

- Not all deployments will have throughput at the same time (the concept taken to the extreme by serverless)

Memory is not compressible. Some tips:

- Be aware of application configuration that affects memory usage. For example, having a needlessly high amount of gunicorn worker processes in a non-prod environment will waste memory.

- Pick node instance types that have high memory vs. CPU. For example the AWS

m5/m6instance families, where am5.largecouples 4 vCPUs to 16 GiB of memory.

A quick cost break-down:

- Let’s assume we use a m5.xlarge spot instance costing ~$70 / month.

- Let’s assume, using the above guidelines, that we can have about 7 feature deploys on a node

- Let’s also assume that, given low throughput, other costs such as network traffic or logging are neglegible

- Per feature deployment, assuming they would be active 24/7, the monthly cost per feature deployment would be $10 / month

- A feature is not active for an entire month. A week would already be long. So, cost per feature deployment is $2.50.

That’s not 0, but it’s not breaking the bank either. Now if we relate that to $100/hr cost of engineering2 you would break even at saving 1.5 minutes of engineering time per feature. Remembering the ‘traffic jam’ dynamics described in the introduction, that should be easy.

This doesn’t take into account the initial setup effort. On the other hand, these calculations also ignore that feature deployments don’t need to run 24/7, and that a week per feature is a high estimate. So we can consider those to be in balance.

Possible improvements

A downside of pipelines is that it can become hard to have an overview and control over what applications are running at any given moment. Constantly adding and removing feature deployments magnifies this problem.

For that reason, ArgoCD has become a tool of choice for many organizations.

When using ArgoCD, an ApplicationSet using the Pull Request Generator would be a suitable way to manage feature deployments.

Conclusion

Feature deployments can help teams move fast by preventing interfering workflows and providing early feedback (shift left). After considering some aspects, such as scope and how to provision the supporting infrastructure, implementation can be straightforward.

Pragmatism and a bit of lo-fi glue code can be all that is needed to get started. This allows teams to evaluate what works and what needs improvement in future iterations.

Don’t hesitate to reach out via Twitter or Mastodon when having any feedback.