How a LEGO restroom sign beats every enterprise software out there

Introduction

To me, ever since occasionally needing to use it, ‘enterprise software’ is the definition of software that makes people feel unhappy. Except perhaps for the people that make money of it. It miraculously gets something done, despite its horrendous user experience, in the process sapping all energy of whoever is forced to use it1.

So, when I recently saw this tweet by Jason Fried, this part resonated well with me:

… because the world is flooded with overpriced, crappy, subpar software. It hurts people, and it hurts the economy.

Agreed.

Shortly after that, while on a long run, I listened to this episode of Lenny’s podcast, featuring Ebi Atawodi. A great episode, ending with the recurring item ‘lightning rounds’, that includes the question “What is a favorite interview question you like to ask candidates?". For product roles, her answer was:

Tell me your favorite product that you are passionate about and why?

Now that’s an interesting one.

Continuing my outdoor run, I gave it some thought, initially focusing on applications. And, although luckily not every application is as awful as described above, nothing really stands out either. But once I expanded the scope to physical products, the question became easy and one answer immediately popped up:

The LEGO House

The LEGO® House, “Home of the Brick”, is a marvelous combination of architecture and industrial design, located in Billund. It is what LEGO calls an experience center.

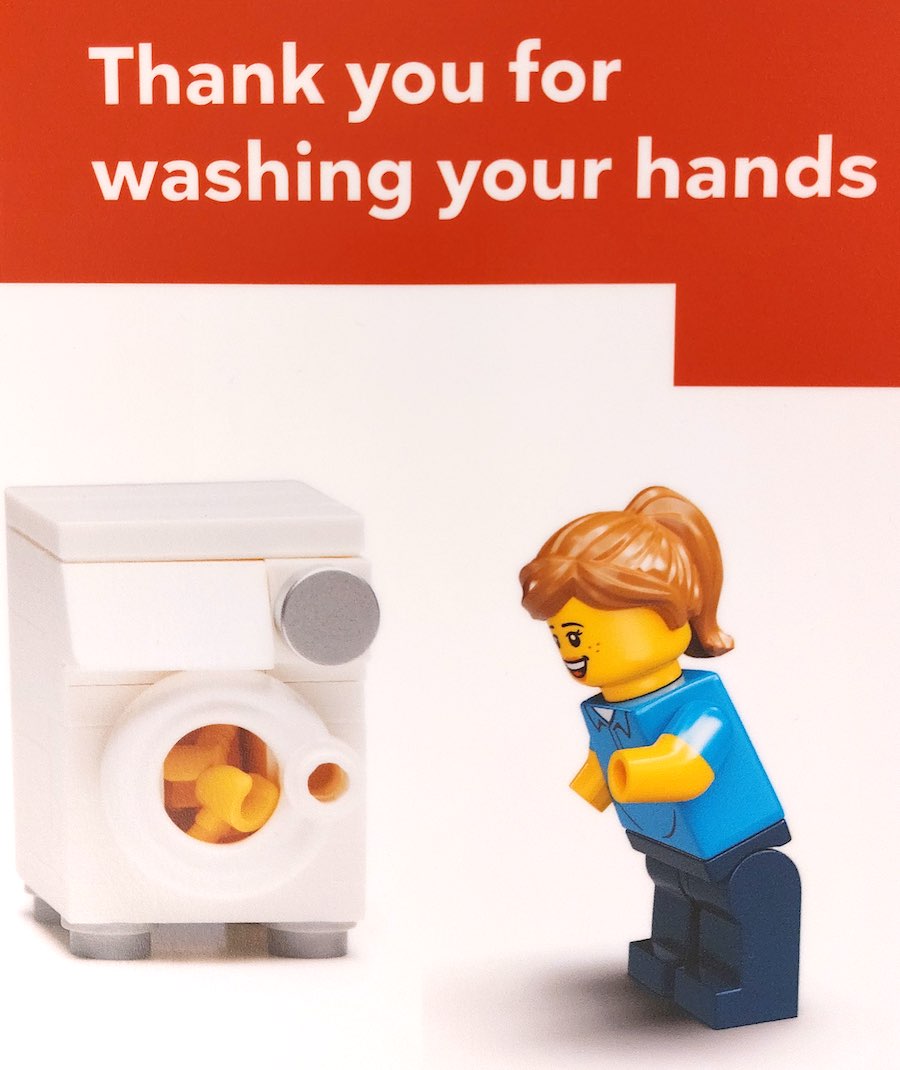

And the stand-out thing that put a smile on my face was, the sign in the restroom, urging visitors to wash their hands.

Thank you for washing your hands

Admitted, I am a fan of LEGO. But even if one is not, there is a lot to appreciate. What is it that sets the LEGO house miles apart from the average software application?

Attention to detail in every aspect

Everything in the Lego house gives the impression that it exists for a reason and is thought through. Of course the large models steal the show, as do the play areas. But wherever you look, the design language is consistent:

- The building itself has the shape of LEGO bricks

- The primary colors of the 4 zones match the oldest primary LEGO brick colors

- As a souvenir you get a set of bricks forming a unique code, molded on the spot

- There is the MINI CHEF restaurant, where you build your orders using LEGO bricks

And yes, this attention to detail goes all the way to the signing.

Whereas in software there can be screen noise (data), in the LEGO House there is real noise (people), distracting from navigation: Where do I want to go? Where do I need to go? Providing guidance through the noise is important.

Attention to details results in consistency, which builds trust. It increases efficiency and helps navigate a product, or building, by reducing cognitive load.

Don’t take my word for it, this article by Dorothy Shamonsky describes the importance of reducing cognitive load, going beyond “it’s just good design”. The Team Topologies approach focuses on reducing (team) cognitive load as well.

Fun, or at least: Pleasant

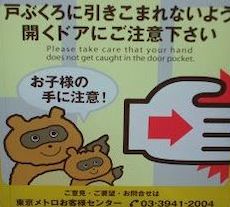

When I visited Japan, one of the (many) remarkable things were the signs in subways, warning to not get your hand stuck between the doors: Cute creatures warning playfully for something very serious.

Watch your hands. Source: Pinterest

The wash your hands sign in the LEGO House has that same energy.

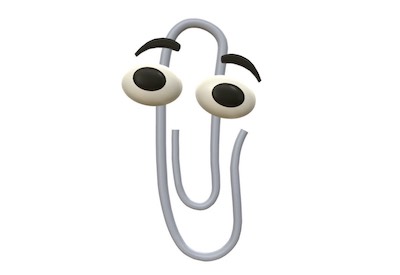

Now, this level of playfulness might not be appropriate everywhere. After spending millions on a CRM, people might find furry animals pointing out the field you forgot to fill in, a bit too much. We all remember MS Office Clippy, right?

But, there is a wide range between playfulness to the point of being over-the-top on the one hand, and cubicle layout levels of awfulness and dread on the other hand. Software, even if the underlying subject is not particularly exciting, does not need to be unpleasant.

Microsoft Office Clippy. Lest we forget.

Confidence

Adding playful elements to otherwise lacking design won’t work. It’s like painting a wooden window frame without first taking care of the wood rot. Exhibit A: The aforementioned Clippy.

But, just like well-placed Easter eggs, if done right, playful elements can convey a message of “We got this sorted, everything under control. We can have a bit of fun here.” Which circles back to building trust.

Taking the user seriously

Most signs urging people to wash their hands, are either questions, or imperative sentences. So there is this little possibility of friction: “Of course I washed my hands!” Or, in case of the imperative form: “What is this sign to tell me what to do?” Luckily not everybody is a snowflake, but still, in a way such signage gives the impression that it is needed to point out to wash your hands.

The LEGO sign takes a different approach: It assumes the visitor has (of course!) washed their hands. And by that message, it elevates the visitor.

I am sure the exact message of the LEGO sign is deliberate, and it illustrates how attention to detail can make a difference.

Improving software UX

So, what can organizations do to make better software?

Beat the economics

This is the hardest part: Apparently crap software can be successfully sold, so why improve? And adding to that: If a company can sell a certain product for a hefty amount, but can also make money on top of that for consultancy and training, there is an incentive to not bother improving software UX.

Another problem might be the small number of alternatives. Take for example office suites. Basically, there is Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace.

An example: I run Microsoft Outlook on my Android phone, mostly to have a calendar widget on one of the home screens. An infuriating aspect is that if corporate policy requires me to re-authenticate, Outlook stays silent. So effectively, I overlook calendar events because the widget becomes outdated. This can easily be solved: Other apps show a system notification in such cases. But as it appears, mediocrity is the norm.

Now, if I were to decide what office suite to purchase, this might be somewhere in the back of my head. But, given many more important requirements, and the lack of alternatives, it will probably not be a deciding factor. Even if I flat out refuse to buy crap software, which I would very much like to, I would need to justify that to higher ups. And alternatives are hardly better.

Feature requirements and pricing make it to the Excel lists when comparing alternatives. But the cost of errors, ineffective work and necessary learning curve, resulting from bad software, is hard to measure. And as a result, those hidden cost are often overlooked.

Once again quoting Jason Fried: “It hurts people, and it hurts the economy”. There is real cost and good UX can be a selling point. But probably more easily an additional selling point than a unique selling point, since buyers tend to focus on hard requirements.

Team composition

User experience design is more than graphical design. So, having someone deliver UI styling now and then, is a start, but is unlikely to accomplish great UX. Within teams, UX skills should be available. Whether that should be via a permanent role within the team, or via an ‘enabling team', depends on the wider organization structure.

Besides UX knowledge being needed within a team, care needs to be taken to facilitate good design across teams. Conway’s law applies here: Not only the technical structure of a system will reflect the social boundaries of the organizations that produced it, the resulting UX might as well. For example, for large retail sites, it is not uncommon to have different teams responsible for product pages, recommendations and the checkout process. There needs to be some entity guarding the overall user experience.

The level of autonomy of a team is an important factor as well. If improving a certain UX aspect requires another team to provide additional data via an API, the resulting UX will most likely be affected by the amount of politics and bureaucracy needed to get that done.

Simplify logic, not just the UI

The more complex the underlying business logic, the harder it will be to create a pleasant UX. This is challenging, especially for applications of a certain age, having gone through many iterations. Not seldom, what starts out focused and consistent, will suffer from an increased number of exceptions. So one needs to be aware that adding features, might have a negative effect on overall usability.

Somewhat similar to programming: When having added things on top for a while, at some point refactoring becomes needed.

It is worth noting that some complexities in business logic, simply can not be avoided, due to compliancy, regulations or privacy requirements.

Do real user tests

Know your users. When working for some time on an application, you get to know the application and the underlying business logic inside out. When thinking about the user experience, that can be a disadvantage, since it becomes harder to look at the product with a fresh perspective.

It can be very informative, and confronting, to invite users in a lab-setup, and let them perform tasks using your application. Let them explain out loud what they do, or record their activities and interview them afterward.

Another great way to test user behavior is A/B tests. This is limited however, to web-based SaaS applications.

X is everywhere

Writing friendly to use software is hard. Not just the discipline itself, but more so the business hurdles that need to be overcome. It starts with wanting, then comes learning and finally comes succeeding.

As long as companies keep trying and succeeding, there will be good software to make visible the hidden cost of bad software. Hopefully buyers take notice.

Users are everywhere. They are not only the users of physical products or software applications. There is customer experience. Or developer experience when using an API, reading documentation, relying on automation or using a developer platform. In all those areas, the X matters.

Thanks for washing your hands!

Thanks for watching your users!

-

Yes, pun intended. And no, there hardly ever is anything voluntary about using enterprise software. ↩︎