Infra pull requests that make a DIFFerence

Introduction

These days, applying Infrastructure as Code (IaC) changes is typically automated by using pipelines or GitOps. This Infrastructure Lifecycle shares some characteristics with the Software Development Lifecycle: It starts with defining a goal, which is then followed by authoring of code, checks and tests, and a code review step.

However, there are also some aspects that make the deployment of infrastructure as code quite different from regular software. These challenges bring risks, which tend to slow teams down. Those risks also limit the practical use of infrastructure as code to the ‘expert’ teams, limiting collaboration within an organization.

By improving our review process we can make infrastructure changes as easy as the continuous delivery of software.

Let’s look into what we can improve, and how this fits into platform engineering and Team Topologies.

You do not want to accidentally replace a database

Challenges

Now what are these challenges, that set IaC delivery apart from ‘just software’?

Challenge: Code change does not equal infra change

When you change the name of a variable within a function, you have a better named variable. However, when you change the name of an S3 bucket in a Terraform project, your bucket will be replaced.

So, there can be a big disconnect between the (small) code change and the actual effect when rolling out the change.

This is aggravated by various abstractions that are used for good reason: Terraform modules, CDK constructs, Helm charts form reusable packages, encapsulating a lot of resources. So, the small maintenance task of bumping the version of a Terraform module, will likely introduce several changes. Now the author of such a module has a responsibility to avoid to unnecessarily break things, but ultimately you are responsible when using the package.

It is worth noting that unexpected changes can also occur when no code has changed. One source, which should be avoided, is click-ops. Another source are automated systems competing for ownership. But an example of a more subtle source I have seen in the past, is AWS ElastiCache automatic minor version upgrades (the default). If other parameters haven’t been set accordingly, you are suddenly faced with a replacement of your ElastiCache setup. Not what you want.

Another mechanism that complicates predictability, is the overlaying of values. For example, Kustomize allows one to use overlays. A great concept, but it can make it hard to predict the effect of a code change on a given environment. To illustrate: Changing a value in a base, might not have any effect on production because it is already defined in the production overlay. This is impossible to predict by looking at the code change alone since that does not show the unchanged overlay.

To summarize:

- Small code changes can have big, unexpected, side effects, such as removal of resources

- Module upgrades bring hard to predict infra changes

- Effect of value overlays is hard to predict

Challenge: Big bang rollouts

In traditional software, we have various methods to safeguard us from production errors. We can run various tests in the CI pipeline, then let the CD pipeline move the same artifact through various environments, up to production1. The production deploy itself then, can use methods such as canary deploys and rolling updates.

Infrastructure changes are different: There is no single artifact that can be moved from environment to environment. Instead, each environment has its own artifact, in the form of the planned changes. There is also no concept of gradual rollout. Furthermore, rollouts are sometimes irreversible or destructive. For example, downgrading a database version is typically not possible.

Of course, changes can be rolled out to non-prod environments first. And this works to some extent. But a change only affecting prod, for example an instance type change, is hard to test. Furthermore, if one doesn’t know exactly what has been changed when upgrading a module, then how can one properly test the effect?

Challenge: Access

Another challenge is access. Assuming we acknowledged the previous challenges, we probably want to preview our changes before submitting a pull request. This often requires a level of access we should not have. This access might be at the network level, authorization level, or both. For example, being able to kubectl diff might not be as simple as one expects, requiring broad permissions. And, while read-only access in a lot of cases seems ok, for secrets it is not.

Improving the workflow

First, let’s look at a basic workflow for infrastructure as code:

Example of a basic infrastructure as code workflow

- Final check: This would typically be a step in a pipeline, right before applying that shows the changes that will be applied. Then in the automation platform, the proposed changes can be confirmed. If something looks not right, this would be the moment where the process is aborted, and a new pull request needs to be created.

- Focus: These are the moments where a second person needs to shift focus to this workflow. The reviewer needs to grasp the intentions of the author, both at the moment of reviewing and when applying the changes. The author might need to chime in when changes are about to be applied, to verify any questions. This task switching is expensive and increases the chance of errors.

- Repeat loops: Repeats can obviously originate from the pull request, but also from the final check. Every repeat loop requires a new pull request. And that will bring more task switching.

- Risk: Just before applying, might be the first time the proposed changes are visible. This requires alignment between the author and the person applying, requiring focus from both. As mentioned before, task switching increases the chance of errors. So, a ‘quick final check’ might not get the attention it needs, and people might overlook important details.

Now let’s see how we can improve this workflow by some relatively small modifications:

- We integrate the proposed changes into the pull request

- We run validating checks on the proposed changes

Example of an improved infrastructure as code workflow

This results in:

- Removed risk: By making the proposed changes available at review time, and ensuring that exactly those changes will be applied, there will be no unexpected changes.

- Reduced task switching: All collaboration is now reduced to a single occurrence: The pull request. The code changes, but also the resulting planned infrastructure changes, are presented in the pull request. This requires the reviewer to change tasks only once, and provides full context.

- First time right: The author, without needing any access or permissions on the target environment, can see the effect of the code changes. This allows the author to fix any issues before submitting the pull request. This greatly reduces the chance of needing additional code changes, and by that a new pull request.

- Guardrails via additional checks: By making the planned changes part of the review, we can run additional checks on the planned changes. For example: Prevent (accidental) deletion of certain resource types, or run policy checks.

In the pull request workflow, the planned changes will augment the code changes, and in most cases even become the focal point of the pull request.

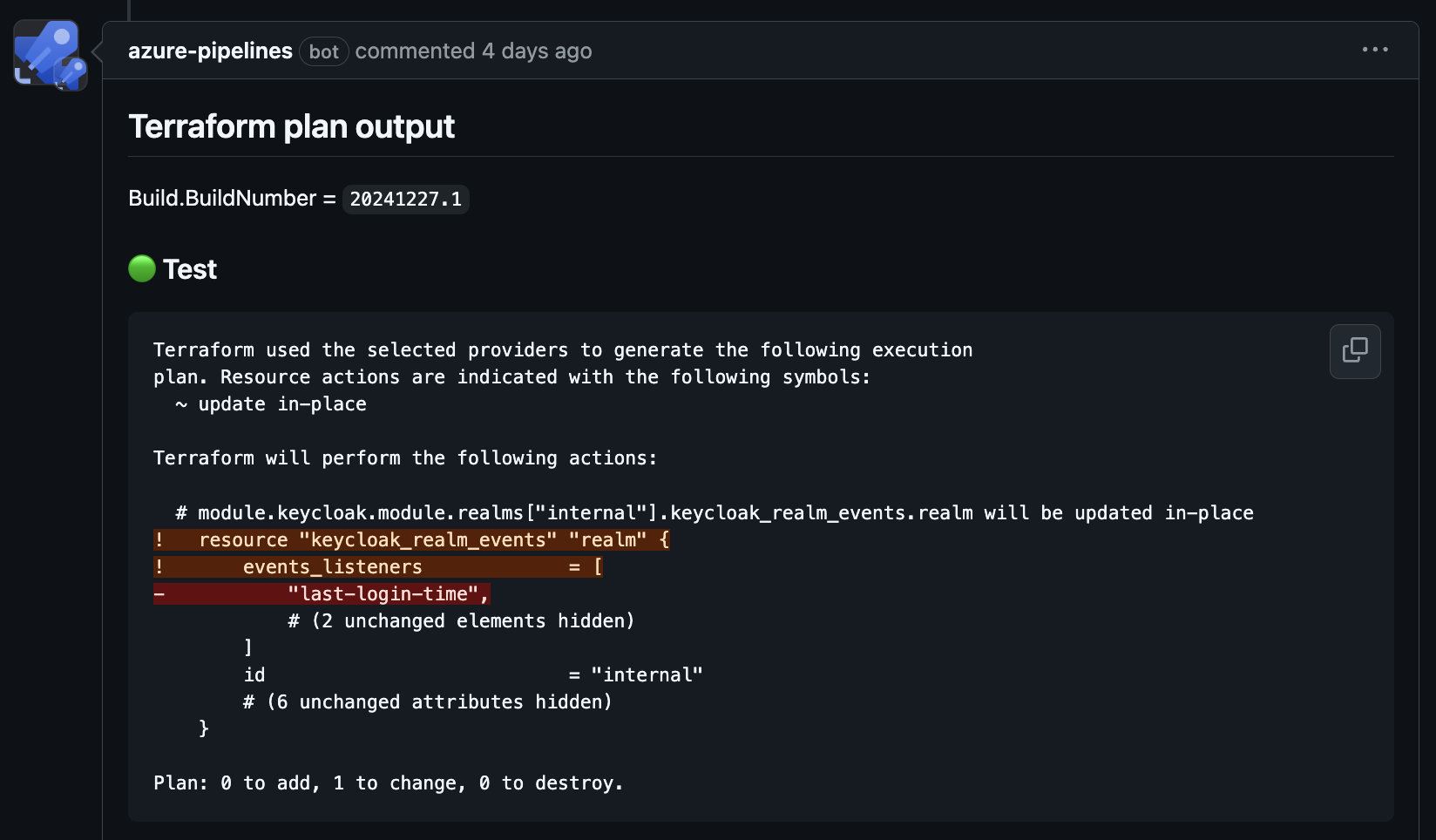

The example below shows terraform plan output in a pull request. Here, apparently, we are about to remove an event listener from a Keycloak realm, which was temporarily added using click-ops to test something2. Without plan output this would either go unnoticed (lack of control) or require further examination at apply-time (increased cognitive load).

Example of Terraform plan output in a GitHub PR

How does this fit into platform engineering?

On the topic of ‘platform engineering’, one is bound to run into the term ‘Internal Development Platform’ (IDP). Quoting one of the definitions that can be found:

An Internal Developer Platform (IDP) is built and provided as a product by the platform team to application developers and the rest of the engineering organization. An IDP glues together the tech and tools of an enterprise into golden paths that lower cognitive load and enable developer self-service.

Gluing together, lower cognitive load, enable self-service… Improving pull requests as described above ticks those boxes. At least to a certain extent.

Depending on who you ask, IDP can also mean ‘Internal Development Portal'. The following defininition is quite concise in explaining how those two relate3:

Internal developer portals serve as the interface through which developers can discover and access internal developer platform capabilities.

An Internal Developer Portal brings and integrates various capabilities: Workflow automation, Service catalog, documentation, dashboards showing a projects health by metrics such as test coverage and vulnerabilities. They typically sit on top of existing services such as version control, or pipelines, and need to integrate with those services. The rewards can be high, but it takes serious investment to start extracting that value.

Focusing on the infrastructure as code part, portals typically require you to identify self-service workflows, then integrate these into the portal. And while that can nicely integrate into the portal, that does not automatically mean integrating into the code review process.

The method described in this article, uses basic building blocks that are likely present in any organization:

- Version control with collaboration, so: GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket and the likes

- CI platform, either integrated with version control (e.g. GitHub actions) or separate, such as Azure DevOps, AWS Code Pipeline, Argo Workflows, etc.

- Infrastructure of code tool of choice. This could be anything: Terraform, Kubernetes manifests via Helm or Kustomize, Cloudformation, CDK, Bicep.

It can be adapted to the systems and tools that are in use, and is relatively easy to implement. Developer experience (DevEx) can be considered good for teams routinely modifying infrastructure as code. To illustrate:

Comparing portal workflows and improved pull requests

Focusing on the infrastructure as code part, a portal has the potential for better DevEx. But the investment of identifying and implementing a workflow might be high. Furthermore, the scope of the improved DevEx is typically limited to the implemented workflows.

Putting a price tag on it: The cost vs. area of improvement of a portal is higher, which can be worth the investment, if the improved DevEx and scale are sufficient.

How does this fit into Team Topologies?

Let’s look at the brief description of Team Topologies:

Team Topologies is an approach to designing team-of-teams organizations for fast flow of value.

One of the four topologies, which can be seen as a ‘kind of team’ is the platform team:

A grouping of other team types that provide a compelling internal product to accelerate delivery by Stream-aligned teams

So: helping stream aligned teams to accelerate delivery. Which can be done by removing some of the friction points an internal developer platform aims to solve:

- High cognitive load

- Ticket Ops / Missing self-service

- Slow delivery

Improving the pull request workflow, as described in this article, benefits the platform team itself, but it can also allow other teams to easily contribute. This puts them back in control over their roadmap. Instead of ‘issuing tickets’ they can ‘create pull requests’. And depending on the situation, they might even be able to self-approve the pull request.

When paired with a curated, opinionated library of packages, such as Terraform modules, CDK constructs or Helm charts, cognitive load can be further reduced: Day-to-day changes then become the mere changing of a limited set of parameters. Optionally, guardrails can ensure the usage of those packages, reducing an organization’s configuration sprawl.

This provides self-service to the stream aligned teams, and the role of the platform team shifts a bit to that of an ‘enabling team’, by providing guidance, and signaling where capabilities of the platform might be lacking.

Additional benefits and complexities

Centering the infrastructure as code workflow around the pull request, addresses the challenges described at the start of this article. There are some additional befits:

- Auditability: Depending on the level of regulation or compliancy that is, your organization might be required to have a ‘change management process’, including a ‘4 eyes principle’ when applying infrastructure changes. Pull requests are already set up for this: Branch protection and required reviewers satisfy the 4 eyes principle, while the closed pull requests, and the rich context provided in those pull request, can serve as an auditable log of infrastructure changes.

- Easier onboarding: There is no need to set up local environments, or access, to start working on systems. Also, it is not required to immediately grasp every abstraction in a project: By changing some variables it immediately becomes clear what the effect will be. Furthermore, previous pull request can provide context and guidance. This helps platform teams when onboarding new team members, but it also helps when performing infrequent tasks.

- Prepare for maintenance: A codebase will see many changes during its lifecycle: Parts evolve, parts might need to be removed. Repetitive patterns emerge that might require refactoring at some point. When this can be done easily, with confidence to not introduce breaking changes, this will positively affect code quality and maintainability in the long run.

Some particular complexities remain though, that might require (quite some) additional effort to tackle:

- What to show? What if the code change affects several AWS accounts? Or: tens or hundreds of edge devices? Depending on the number of targets, it might be needed to select a representative example to show the planned changes. This implicitly requires the targets to be set up identically, following logical patterns. Identifying what to show, or how to spot outliers, can be challenging.

- Noise: When comparing current and intended state, certain types of metadata might create noise. This could be metadata changes in the actual state, or changes introduced in automation. Depending on the nature, this could make the actual changes less obvious.

- Apply time errors: In most cases, tools will identify syntax errors or misconfigurations. There are however errors that will only show once trying to apply the change. For example, the name of an AWS security group needs to be unique within the VPC. In some cases this might be indicative of an underlying problem: A lack of naming conventions that ensures uniqueness. For other cases, one could consider adding checks in the pipeline that ‘shift the problem left’.

Conclusion

Augmenting pull requests with planned changes and leveraging policies, is hardly revolutionary: Platforms such as Terraform Cloud and Spacelift offer similar capabilities. Self-hosted, for Terraform, one could consider Atlantis. Since September 2024, AWS Cloudformation has this capability as well.

While such platforms, or internal developer platforms in general, are very compelling, there are things to consider: SSO integration, RBAC models, the migration of existing workflows, ‘do we need local runners with sufficient network access?', ‘where does our data go?’ and ‘who has the keys to our castle?'. To name a few.

A lot of those topics might already have been addressed with the existing pipeline and git workflow tools that are used. Maximizing their value then is something that can be implemented today, unlike procurement of a platform which arrives no sooner than tomorrow. And, it can be done with pretty much every IaC tool: Terraform has a plan step. Kustomize and Helm offer diff capabilities. So does CDK, and Azure’s Bicep has a what-if operation.

This article illustrates how relatively simple improvements can deliver a lot of value. If finding this interesting, I encourage you to read my previous blog post about ‘Terrible’: It describes an in-house tool that allowed teams to run Terraform and Ansible with confidence for many years. As this article shows, these days there would be no need to build such a tool, since better DevEx can be accomplished with the basic DevOps building blocks every organization already uses.

In a next article I will go more in depth into the technical aspects of integrating infrastructure as code, pipelines and GitHub.

Hopefully this gives inspiration to look at one’s DevOps workflows and spot possible improvements. If wanting to discuss, be sure to find me on LinkedIn or BlueSky. Thanks for reading!

-

This assumes separated CI and CD pipelines. A good practice, but in reality these are often intertwined in a single pipeline. Nevertheless, there are steps that build (CI) and steps that deploy (CD). ↩︎

-

Shame. Shame. Also: Pragmatic. But one needs to be aware the click-ops change can be reverted at any moment and can thwart others workflow by showing unexpected changes. ↩︎

-

This blog post by Humanitec, themselves an IDP vendor, gives some context on the platform/portal confusion of IDPs. ↩︎